The quiet life

I was learning fast that Goa’s dissimilarities with the rest of India went far deeper than the buildings and the food. I kept hearing Goans talk about India as if it was a foreign country, and vice-versa. And, especially in Panaji, there is a laid-back, distinctly Mediterranean tempo, with church bells chiming away the hours – every other city I’d been to in India was characterised by noise and frenzy. There is a term for Goa’s easy-going approach to life: susegad, a Konkani word deriving from the Portuguese for ‘tranquil’ (sossegado).

I needed to venture further afield to be reminded that Goa remains part of India. The Hindu temples – and the odd mosque – that dotted the town of Ponda offered a clue that this inland region was only incorporated into Portuguese India 250 years after the colonists arrived. Crucially, the days of forceful Catholic proselytisation had by then segued into relative religious tolerance. Susegad felt like a distant dream at the Shri Mangueshi temple, where I joined throngs of barefoot pilgrims from all over India, bowing in devotion before an incarnation of Shiva amid clashing cymbals, flames, chanting and the smell of sandalwood.

Still, Ponda’s other draw – its spice plantations – bear testimony to the lucrative trade that brought the Portuguese to Goa in the first place. The one I went to doubled as a tourist operation, with cultural shows as well as walks through the forests, where cardamom, turmeric and nutmeg are cultivated.

Cashew trees became the main crop as I headed deeper into the hinterland. The nuts are delicious, but the main reason they are grown here is for their colourful, apple-sized fruit, which are mashed, fermented and distilled into the feni firewater, often offered on the house after a restaurant meal. Silage-like whiffs wafted from crude, open-air distilleries as we snaked high up into Chorla Ghats, a forested range of waterfalls and wildlife that forms Goa’s natural border with the states of Maharashtra and Karnataka.

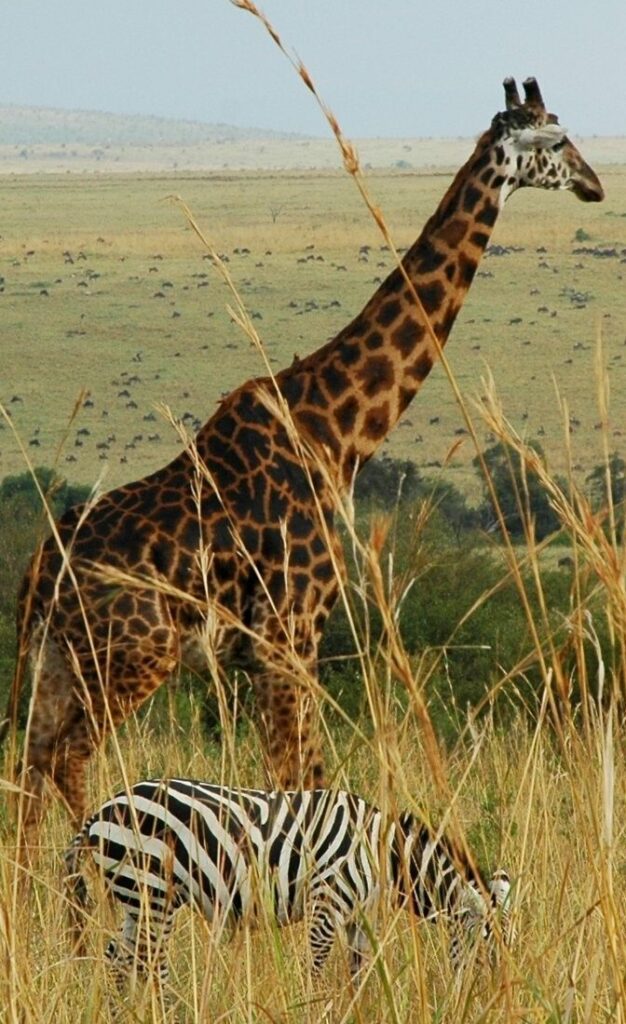

The British would no doubt have built ahill station and a narrow-gauge railway to get there. However, the Portuguese colonists were less interested in the unpopulated extremes of their territory and left no trace in these mountains. I stayed at the recently built (and wonderfully named) Wildernest Nature Resort, a scattering of unfussy wooden bungalows and a beautifully discreet infinity pool sculpted from the mountainside, as if nature had intended it. There are barking deer, sloth bears and even leopards in the forest, though these proved elusive. But dawn on my balcony, watching troupes of monkeys swinging through the trees and graceful hornbills gliding by, was a moment of magic. Crimson sunset atop Swapnagandha (meaning ‘fragrance of dreams’) hill was another.